This, my bric-a-brac World

e.e. cummings said, “it’s always ourselves we find in the sea.” Bring a passel of boys to a beach, and see how true this is: one group will splash in immediately, challenging the water physically, dunking and wrestling each other; another group will sit by the edge, glorying in the wet sand, flinging mud, digging with abraded hands, working to shape the muck into walls and towers. Others will turn to the sports equipment, or try their hand at backflips or roundoffs, waxed brave with the forgiving softness of the sand beneath them. These boys all, in different ways, are lost in wondering at themselves, testing their physical strength, getting to know the measure of their mortality. But often enough, there is another sort, who wanders off, bending first for a moment here, sitting on his haunches there. After some time, he will return, hands (and pockets) full of the bric-a-brac of the sea: shells, sea-glass, pebbles, crab-claws, starfish, kelps, gull feathers, the spectrum of relics marooned by the unreckoning ocean. He too is wondering, and sizing himself up against the natural world, but pitting his mind, rather than his muscles against it. He will name it, number it, categorize it, apprehend it. He will, in a word, collect it.

Boys have always been collectors. From coins to comics, baseball cards to bottle caps, boys’ brains seem hardwired for it, and the men they become often don’t lose the trait, (as many wives can attest). They will impress each other not with the volume of a collection only, but also the intimate knowledge they have of their given subject matter.

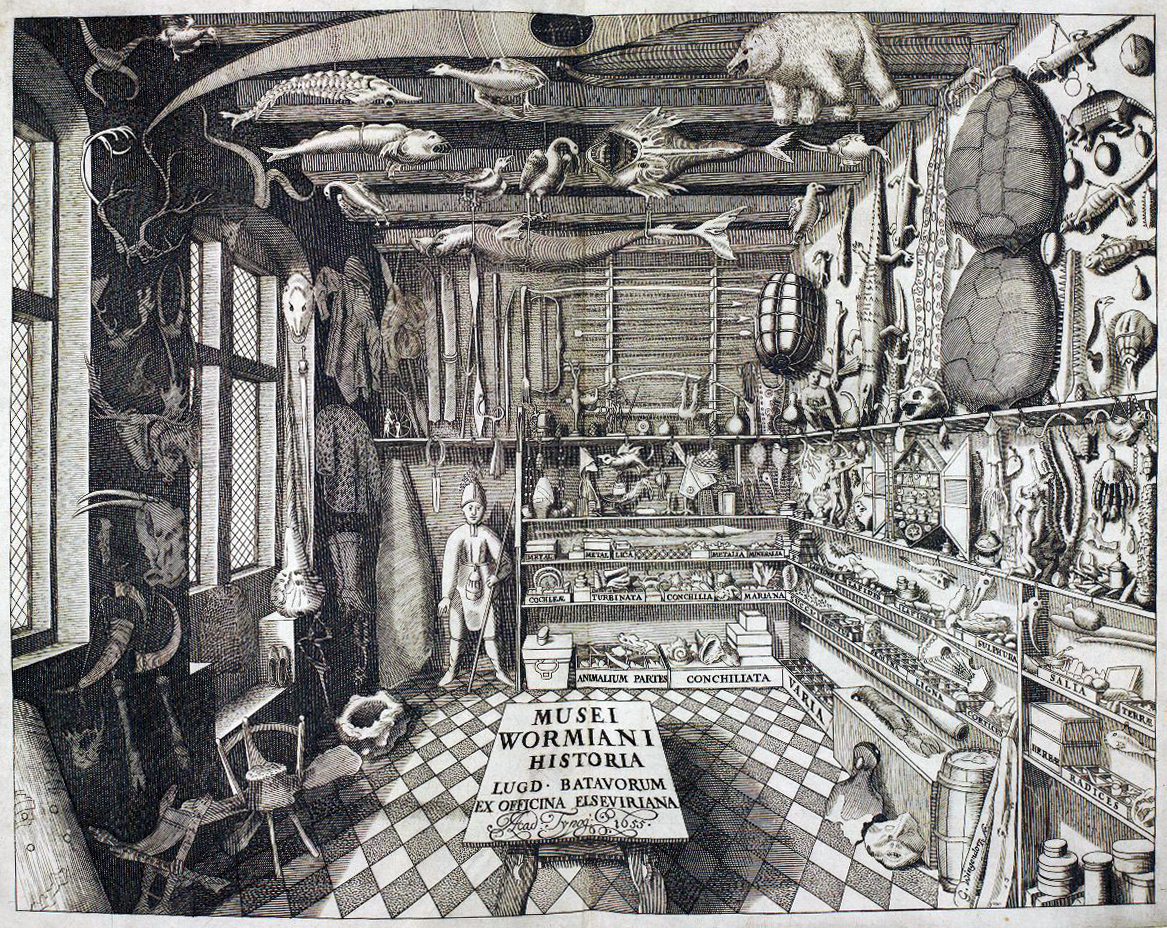

During the Renaissance, long before Google, people would who didn’t want to travel months to foreign lands in leaky boats in order to know the world, went to their enlightened kings and emperors, to get a look at the “kunstkammer,” his cabinet of natural history. This cabinet was not a piece of furniture, but an entire room, stuffed top to bottom with objects that we now put in museums. The most famous of these was that of Ole Wurm, (or Olaus Wurmius), an engraving of which is to your

left. Skulls, and skeletons, animals, stuffed and mounted, rows of tortoise shells, and shark’s teeth, horns, hung, or mounted, a riot of oddities, kept for study and contemplation. This was a room where science and philosophy held discourse. In this room the unicorn was confined to myth, and the narwhal known.

Over time, naturalists would create their own small “cabinets”, with specimens from the new world. These would become the curio-cabinets, symbols of wisdom and experience, of universal and peculiar knowledge, of an expansive and liberal mind.

To get back to the modern day, and to your son, his pockets bulging with rocks, rubberbands, bugs, alive and dead, and the rest of it. Nature has given your son a collector’s heart and obligingly set out a plethora of materials for study, and all for a small investment of a walk together in the woods, or on the beach. Set aside a curio for him, a case or cabinet, where he can display his wonders: cicada husks, snakeskins, wasp’s nests, honeycombs, feathers, fossils, bird nests, seed pods, pinecones, acorns, coral, quartz, butterflies and birch bark. Look them up, learn about them, label them, in English and Latin. Help your young grubber pair his inclination toward mental (and physical) accumulation with the splendors of the natural world, and you will have something special: a gallery in which each collected item is a peek at the gears of the world, a keyhole view of God’s attic, a backstage pass to the mysteries of the universe.