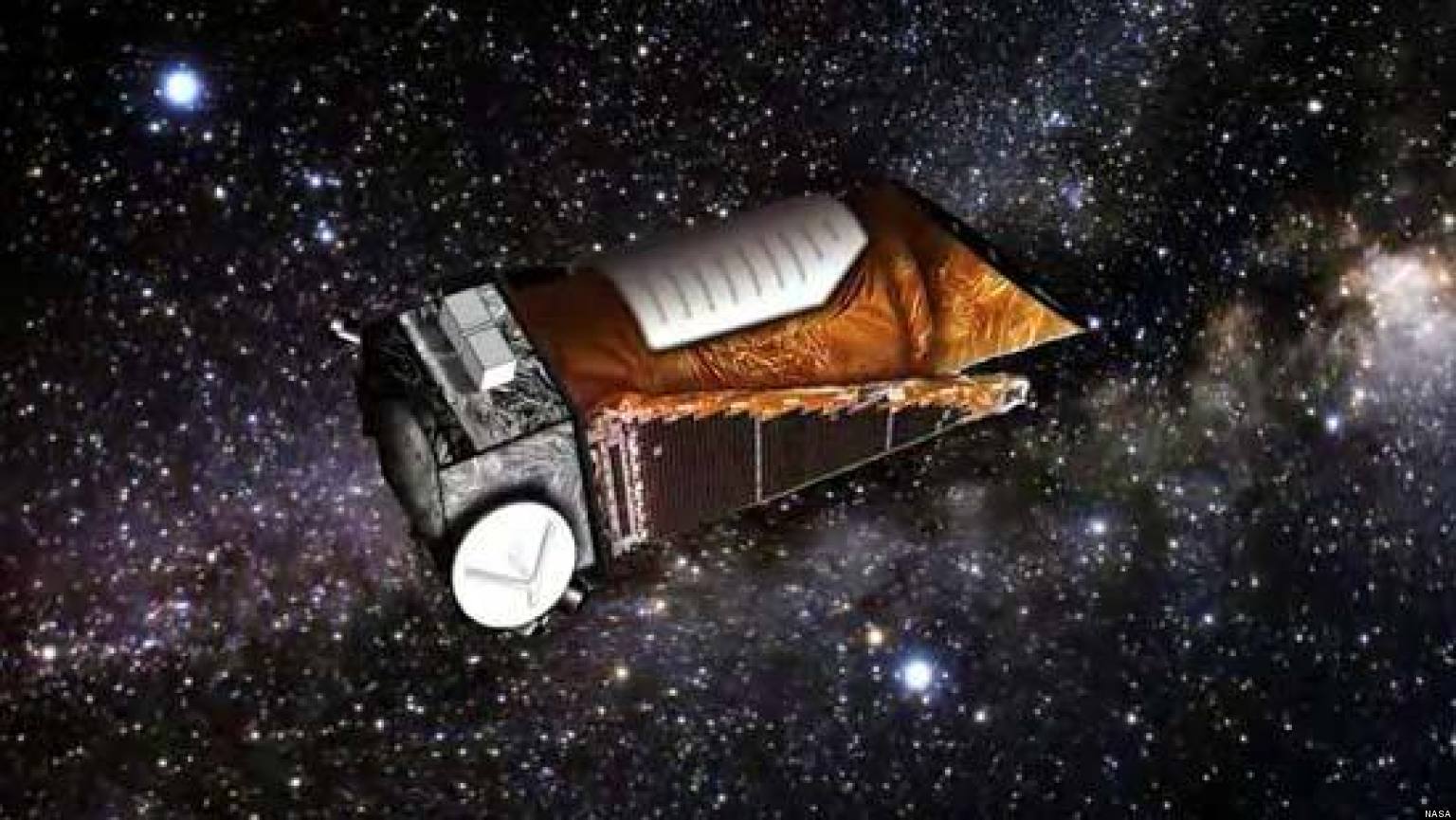

Whooooosh! Did you see me coming? It’s me, Spaceman Spiff! For this blog, I’m writing about the Kepler Space Telescope, my personal favorite, (at least, as far as satellites and space telescopes go).

Kepler was launched on March 7, 2009, and it was named after renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler. Its mission is to help us solve a question that has plagued humanity for centuries: Are we alone?

To do this, you need to find planets. But this is easier said than done, because of the fact that planets don’t give off any light (at least not the rocky ones, and as far as we know, those are the only ones that can support life). But the planets do block some of their star’s light. If you can detect a star dimming, and record it happening every, let’s say, two weeks, you’ve found something orbiting a star, possibly a planet!

With this information, you can find out a lot, like how long it takes the planet to orbit its star (obviously), how far away from its star it is, and if you know how far away the star is, how big the planet is. (You can also find out if it is a planet in the first place.) However, it takes incredibly sensitive instruments. It’s hard, but Kepler has the tools to do it! Speaking of which, we should probably get back to it.

Unlike Hubble and other telescopes, Kepler was made to point at part of our area of the Milky Way. It even orbits the sun, not the Earth (but keeps close to the Earth, otherwise it would lose radio contact). Its single photometer measure the brightness of stars, and sends the information back to Earth, where it is processed to detect the dimming of stars, the crucial information for detecting planets.

The length of the mission was expected to be three-and-a-half years, but by 2012, it was expected to go on until 2016 (the year we’re in now, happy new year!) However, in the same year, two out of Kepler’s four reaction wheels failed, rendering Kepler unable to point at one spot in the sky. In 2013, NASA gave up trying to fix the reaction wheels, and declared Kepler dead (I don’t know how they could have done it, partly because my ship doesn’t use reaction wheels).

However, in 2014, some ingenious scientists at NASA got the idea to use the Solar Wind (the radiation coming from the Sun) plus the two working reaction wheels to give Kepler a changing but steady view of the elliptic-the path the Sun takes through the year. It can’t be pointed anywhere else because then Solar Wind wouldn’t help any more. Although Kepler will be restricted to planets orbiting the brightest and closest stars, it will still be able to detect Super Novae in faraway galaxies, and possible killer asteroids.

Kepler is an amazing machine, and will always be remembered as a great achievement in space exploration.