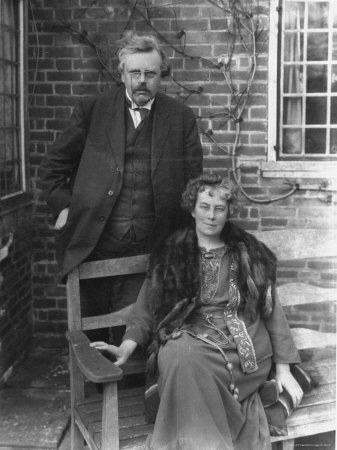

One of the great writers of the 20th century, G.K. Chesterton, is one of Riverside’s patrons. On this wonderful day when we celebrate and remember our mothers, I share with you an excerpt from Chesterton’s book What’s wrong with the world. In one of his essays, with his usual merry wit and penchant for paradox, the merry bard speaks of the grand adventure of motherhood. All of us–and since this blog is about boyhood, I will say every boy, learns first about this wonderful life from his mother. Her glance engenders love in his heart and makes him more capable of living a life connected to the greater narrative of the human family. Though part of boyhood requires those challenges and journeys away from the home–so that he may test his mettle like the great heroes of old–all heroes have their roots in a home and their hearts with their mother. Though great adventures await the lads of this wild land, they will soon be lost if they forget she who formed their universe.

The following is from What’s Wrong with the World. Chesterton answers the feminist criticism of domesticity with the wit for which he is famous!

“Babies need not to be taught a trade, but to be introduced to a world. To put the matter shortly, woman is generally shut up in a house with a human being at the time when he asks all the questions that there are, and some that there aren’t. It would be odd if she retained any of the narrowness of a specialist. Now if anyone says that this duty of general enlightenment (even when freed from modern rules and hours, and exercised more spontaneously by a more protected person) is in itself too exacting and oppressive, I can understand the view. I can only answer that our race has thought it worth while to cast this burden on women in order to keep common-sense in the world. But when people begin to talk about this domestic duty as not merely difficult but trivial and dreary, I simply give up the question. For I cannot with the utmost energy of imagination conceive what they mean.

When domesticity, for instance, is called drudgery, all the difficulty arises from a double meaning in the word. If drudgery only means dreadfully hard work, I admit the woman drudges in the home, as a man might drudge at the Cathedral of Amiens or drudge behind a gun at Trafalgar. But if it means that the hard work is more heavy because it is trifling, colorless and of small import to the soul, then as I say, I give it up; I do not know what the words mean.

To be Queen Elizabeth within a definite area, deciding sales, banquets, labors and holidays; to be Whiteley within a certain area, providing toys, boots, sheets, cakes and books, to be Aristotle within a certain area, teaching morals, manners, theology, and hygiene; I can understand how this might exhaust the mind, but I cannot imagine how it could narrow it. How can it be a large career to tell other people’s children about the Rule of Three, and a small career to tell one’s own children about the universe? How can it be broad to be the same thing to everyone, and narrow to be everything to someone? No; a woman’s function is laborious, but because it is gigantic, not because it is minute. I will pity Mrs. Jones for the hugeness of her task; I will never pity her for its smallness.”